Understanding the importance of equine gut health

Your horse’s gut plays such an important role in maintaining health and well-being. The equine gastrointestinal tract works hard digesting feedstuffs, making essential nutrients that the horse cannot produce on its own, protecting your horse from disease, and even shaping horse behaviour. Thus, it is vital to maintain gut health in horses and to ensure you are managing your horse in a way that promotes equine gut health, through an understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the equine digestive system.

Gut health plays a key role in promoting your horse's health and well-being

Overview of the equine gastrointestinal tract: anatomy and function

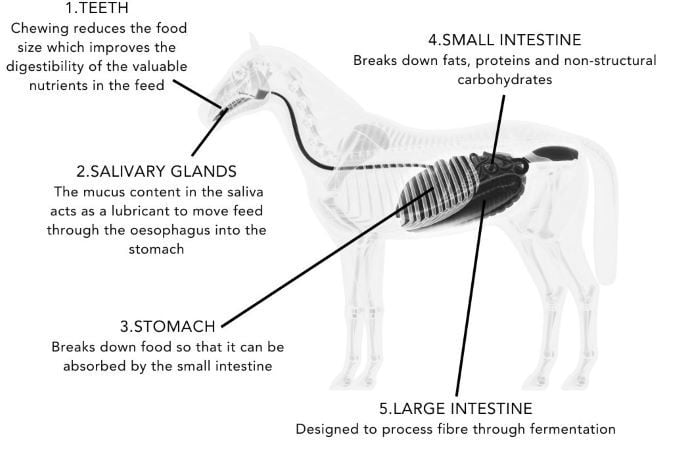

The horse has a digestive tract that consists of the foregut (stomach and the small intestine) and the hindgut (large intestine).

1. The Foregut: Stomach and Small Intestine

The foregut in horses is similar to the pre-caecal digestive system of a monogastric animal, such as a dog, human, or pigs. This section includes:

- Stomach: The horse’s stomach contributes to only eight percent of the total digestive tract weight. It has a capacity of approximately eight litres in a mature 500kg horse.

- Small Intestine: Comprises three functional regions: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum, which together account for around 30% of the total tract mass, but is 75% of its total length.

Diagram of a horses digestive system

2. The hindgut: large intestine and fermentation

The hindgut makes up about 60% of the gastrointestinal tract volume, consisting of the caecum and the large and small colons. This section is crucial for degrading and fermenting the fibrous fraction of plants.

Fun fact: The horse proportionally has the largest hindgut of any domestic animal!

The importance of saliva for your horse’s gut health

The digestive process in horses begins in the mouth, where the first steps of breaking down food take place and is why regular dental care is so important. The incisor teeth, located in the middle area of the upper and lower jaw, cut down vegetation, while the premolar and molar teeth on the sides of the jaw grind the food into smaller pieces, making it easier to digest.

Chewing is such an important aspect of digestion as it reduces the feed size which improves the digestibility of the valuable nutrients in the feed. Secondly, horses only produce saliva as a direct result of chewing and therefore if the horse is not chewing then no saliva is being produced, which can impact on the health of your horse’s stomach.

Horses chew more when eating forages compared to when they are eating concentrates (Meyer et al., 1985). This means higher levels of saliva is produced when eating forages, this is likely due to the larger size of the feed and also can be related back to the moisture levels compared to concentrates. As a result, forage feeding promotes the production of more saliva, which helps protect the stomach lining and supports overall digestive health

Why Is Saliva Important for Digestion?

Saliva is produced as a direct response to chewing and contains little to no digestive enzyme activity in horses (Frape, 2010). However, its mucus content acts as a lubricant to support the passage of the feed to transport through the oesophagus into the stomach.

Forage promotes the production of more saliva which aids efficient digestion.

The structure of a horse’s stomach and its role in the digestive process

The role of the horse's stomach is to breakdown food so that it can be absorbed by the small intestine. The stomach is divided into two main sections: the non-glandular region (upper part) and the glandular region (lower part). Each area plays a unique role in the digestive process.

Non-Glandular Region:

The non-glandular region of the stomach relies heavily on saliva that is swallowed with food to maintain a neutral pH of between 6 and 7. This part of the stomach lacks a mucous layer for protection, and when the pH drops and becomes too acidic, the stomach lining is at risk. This can result in the formation of gastric ulcers.

Glandular Region:

The glandular region has a much lower pH, ranging between 1.5 and 2, and is naturally protected by a mucous layer. This helps safeguard the stomach lining from the acidic environment.

The risk of gastric ulcers and how to prevent them

Over 90% of racehorses are estimated to have gastric ulcers (Bell et al., 2017), and the prevalence in non-racing disciplines ranges from 40 - 60%. There is evidence to show that horses left for longer than 3 hours without access to forage are at greater risk of developing gastric ulcers. Furthermore, horses fed large amounts of cereal grains, which take less time to chew, and lower amounts of forage, are also much more likely to develop gastric ulcers. Lastly, exercise can also have an impact on gastric ulcers as there can be ‘splashing’ of acidic contents from the lower part of the stomach to the sensitive upper part of the stomach, resulting in the formation of ulcers.

To maintain your horse's digestive health and prevent gastric ulcers, ensure that your horse always has access to forage, feed them smaller, more frequent meals, and avoid heavy grain-based diets. It is also beneficial to allow access to forage before exercise or feed a small meal of chaff before exercise.

For more information on gastric ulcers, visit our detailed guide: Gastric Ulcers in Horses.

What does the horse’s small intestine do? (In the Foregut)

The digested food leaves the stomach and enters the small intestine where it is mixed with intestinal secretions that maintain a neutral environment (pH 7) and break down fats, proteins and non-structural carbohydrates (starch and sugars).

The protein digested in the small intestine is of direct benefit to the horse as any undigested protein travels to the hindgut and is used as a substrate by the microbiota (bacteria, fungi, and protozoa, also referred to as microbes). The horse has a limited capacity for starch digestion and any starch not digested in the small intestine will also travel to the hindgut where it will be fermented by the microbes. Cereal grains (oats, barley, maize) need to be processed in some way otherwise the starch present in these grains is less digestible in the small intestine. The horse does not produce enzymes to break down sugars in the small intestine.

Sugars are present in grass, and since this cannot be digested in the small intestine it travels to the hindgut. High levels of starch or sugars in the hindgut environment can be disrupted and can lead to various conditions such as Laminitis, Colic, and hindgut acidosis (Bailey et al., 2004). It is recommended that no more than 1g starch per kg body weight is fed per meal (Harris & Dunnett, 2018).

What happens in the horse's large intestine? (The Hindgut)

The large intestine contains only mucus-secreting glands which do not produce digestive enzymes. This means the hindgut is solely dependent on the micro fermentation of undigested food which has left the small intestine. The hindgut is designed to process fibre however problems can appear when non-fibrous substances like sugar and starch enter.

Fatty acids, produced from the breakdown of food, are absorbed across the gut wall and used as an energy source by the horse. However, microbial populations within the stomach, including those associated with fatty acid production, are highly sensitive. Sudden changes, such as a shift in diet, can disrupt these populations, potentially causing stomach issues like colic by affecting the gastrointestinal tract.

Summary:

- Feed a high-fibre diet, with a forage-first approach and then add in any additional feedstuffs only where required.

- Only if required, feed high-starch concentrate feeds little and often and avoid large bucket feeds of starchy foodstuffs.

- Make any changes to the diet gradually over a period of two weeks.

- Maintain a healthy weight and condition in your horse(s) and monitor on a regular basis.

- Make any management changes gradually, e.g. amount of time in the stable or at pasture.

- Allow access to forage before exercise or feed a small meal of chaff before exercise.

- Ensure a balanced diet to maintain gastrointestinal health.

For any advice or questions you may have, please don't hesitate to reach out to our expert nutrition team. You can call 0800 585525 Monday-Friday 8:30am-5:00pm. Email [email protected], or send us a DM on social media.

References:

Bailey, S.R., Marr, C.M., & Elliott, J. (2004). Current research and theories on the pathogenesis of actute laminitis in the horse. Equine Veterinary Journal, 167: 129-142. doi:10.1016/S1090-0233(03)00120-5

Begg, L.M., & O’Sullivan, C.B. (2003). The prevalence and distribution of gastric ulceration in 345 racehorses. Australian Veterinary Journal, 81(4): 199-201. doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.2003.tb11469.x

Frape, D. (2010). Equine Nutrition and Feeding, 4th Ed. Wiley-Blackwell, UK.

Garber, A., Hastie, P., & Murray, J.-A. (2020). Factors influencing equine gut microbiota: current knowledge. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 88: 102943. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2020.102943

Harris, P., & Dunnett, C. (2018). Nutritional tips for veterinarians. Equine Veterinary Education, 30 (9): 486-496. doi.org/10.1111/eve.12657

Hintz, H.F., Argenzio, R.A., & Schryver, H.F. (1971). Digestion coefficients, blood glucose levels and molar percentage of volatile acids in intestinal fluid of ponies fed varying forage-grain ratios. Journal of Animal Science, 33(5): 992-995. doi: 10.2527/jas1971.335992x

Meyer, H., Coenen, M., & Gurer, C. (1985). Investigations of saliva production and chewing in horses fed various feeds. Proceedings of the Nineth Equine Nutrition and Physiology Society, East Lansing, Michigan, UK: 38-41.