Multiple factors influence the health and quality of our horse’s hooves, and as the old phrase goes “no hoof, no horse”. A survey conducted by Thirkell & Hyland (2017) shows that hoof issues are extremely common, with 89% of UK horses experiencing hoof problems in the last 5 years, therefore it is important to focus on hoof health. The external environment of the hoof influences its structures, with excessively dry conditions being associated with brittle hooves that are prone to chipping and cracking, whilst excessively wet conditions are associated with soft soles. A wet environment does not appear to influence the moisture level of the hoof wall but is thought to increase the incidence of white line disease due to the effects on the sole (Hampson et al., 2012; O’Grady & Burns, 2021). Providing access to a dry area where your horse can spend some of its time is helpful in supporting hoof health, alongside regular cleaning and routine trimming by a qualified professional.

Image: Farrier trimming horses hoof

Hoof quality and growth is influenced internally by the horse’s genetics and the nutrients it consumes. Genetics are difficult to influence, although some issues such as hoof wall separation disease (HWSD) that affects Connemara ponies, can be reduced by testing for the genetic mutation and not breeding affected animals (Logie, 2017). We know that some horses seem to naturally have strong healthy hooves whilst others struggle with poor hoof quality, with some breeds seeming predisposed to inferior hoof horn quality (Josseck et al., 1995). Aside from genetics, the key to growing strong healthy hooves is feeding a balanced diet that provides all the components required by the body to make the hoof structures. However, for horses and ponies that struggle with weak hoof horn or that have slow hoof growth, providing certain nutrients at higher levels can help the body to produce strong hoof structures. The beneficial effect of feeding such nutrients on hoof quality may not be seen for several months, not because they have no effect, but because mature horses’ hooves grow relatively slowly at a rate of 8-12mm per month, meaning it can take 9 to 12 months for changes in hoof quality to be seen (Frape, 2010).

INFLUENCE OF NUTRIENTS ON HOOF HEALTH

A balanced diet means your horse consumes all the nutrients its body requires to maintain health and perform any physiological functions required, such as repair of tissues, growth, exercise, or reproduction. A balanced diet ensures all required nutrients are consumed in appropriate quantities to meet demand but not impair the absorption or function of other nutrients, which can lead to nutrient deficiencies (NRC, 2007). Nutrients are classified into six main categories: water, fats, carbohydrates, protein, vitamins, and minerals. To survive the horse needs to consume specific nutrients from each of these categories, plus energy, although energy is not classed as a nutrient as it is gained from the processing of carbohydrates, fats and proteins (McDonald et al., 2011). Vitamins are organic substances which can be found in the horse’s forage and concentrates, and minerals are inorganic elements that come from water and soil that are then absorbed by plants and consumed by the horse. Minerals can be categorised into macro minerals and micro minerals (also known as trace elements), based on the amount they are required in the diet (McDonald et al., 2011).

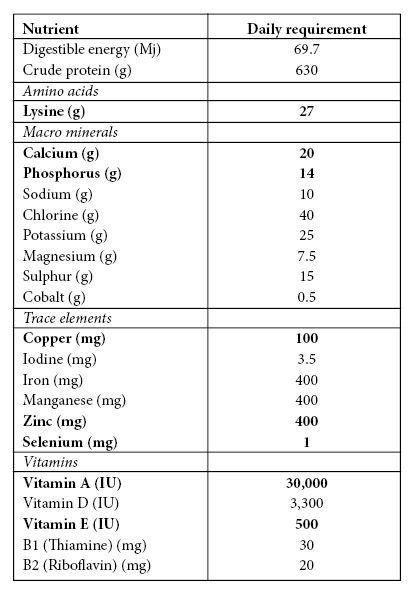

It is the balance and the combination of these nutrients that will improve hoof health and growth, as some nutrients in excess can be detrimental to hoof development. Table 1 shows the nutrient requirements for a 500kg horse at maintenance consuming 10kg of food per day (as dry matter), equivalent to 2% of its body weight. The stated requirements are the minimum values for a balanced diet to keep the average horse healthy, with nutrients that play a key role in the health and growth of the hoof shown in bold. We will take a look at these nutrients in more detail.

Table 1. Nutrient requirements for a 500kg horse at maintenance fed at 2% body weight

Calculations based on NRC (2007) recommendations

ENERGY AND FOOD INTAKE

All horses are recommended to be fed 2% of their body weight daily on a dry matter (DM) basis, with at least 1.5% of their body weight being fed as forage, although higher forage intakes are ideal for general and digestive health. Feeding less forage than this is likely to cause problems such as gastric ulcers and colic, and could be detrimental by way of lack of correct nutrients for hoof health. If horses are in negative energy balance, either purposefully due to being on a diet, or due to an inappropriate food intake, they will first utilise their body fat stores with the potential of then using their protein stores to provide energy, thus reducing the availability of protein to support hoof health, which can have detrimental effects on hoof health as we will later discuss. A study by Butler & Hintz (1977) showed a 50% greater growth in the hoof wall with ponies fed a positive energy balance compared to those on restricted diets. Such findings indicating that equids on a restricted diet may benefit from feeding additional nutrients.

A study using 48 horses by Ley et al. (1998) over a 12-month period showed that seasonal movements and nutritional regimes significantly affected the strength of the horses’ hoof wall as well as its mineral composition. Horses fed a more balanced diet, according to the NRC recommendations at the time, had greater hoof tensile strength, showing that a forage-only diet is unlikely to provide the horse with sufficient nutrients for a balanced diet, and that horse owners should consider ways to feed nutrients that will optimise hoof growth rate and quality horn production.

In a study by Jancikova et al. (2012) horses supplemented with vitamins, minerals and amino acids had 22.3% higher hoof horn growth with sufficient quality, than a control group of horses not being fed the supplement. These findings support an earlier study Butler & Hintz (1977) which reported a 50% increase in hoof horn growth rate when ponies were fed an ad libitum pelleted feed compared to those with a restricted ration. Although this type of feeding may not be appropriate for all horses and ponies, it does lead us to believe that those on a restricted diet would benefit from supplementation of certain nutrients.

Image: Oiling the horse's hooves

PROTEIN AND AMINO ACIDS

The hoof comprises mainly of keratin, a protein made of amino acids which contributes to the durable structure of the hoof wall (Frandson & Spurgeon, 1992). As the horse is not able to produce all the amino acids it requires, some amino acids must be supplied in the diet, these are referred to as essential amino acids. Amino acids are the building blocks of protein, with Lysine being the first limiting amino acid, meaning it is the amino acid that is likely to first become deficient in the horse’s diet (McDonald et al., 2011). When Lysine is deficient, the synthesis of proteins within the body is limited, even if all other amino acids are present in adequate amounts. As such, it is essential to provide adequate Lysine in the diet, with some good sources being Soya bean meal, Spirulina and Fenugreek seeds. Providing Lysine alongside amino acids Threonine and Methionine within the diet will aid keratin synthesis and optimise hoof quality.

Methionine is frequently recommended and can be found in many feeds (alfalfa, sugar beet pulp, rice bran) and supplements. Methionine is important because the horse converts it to Cystine, an amino acid which provides keratin with its structure and durability, however Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) must also be present in the diet to allow this to happen (Kellon, 1998). Methionine and Cystine are Sulphur-containing amino acids, a macro mineral also required for keratin growth (Jancikova et al., 2012). Care must be taken not to over supplement the horse’s diet with Methionine as it is possible that this may reduce the absorption of Copper, Zinc and Iron (Anon, 1998), leading to white line disease and degeneration of the hoof wall.

A diet that is protein deficient can lead to a slower rate of hoof growth as well as cracking and splitting (Lewis, 1995; NRC, 2007). It is unlikely that a UK forage only diet, especially if limited or no grazing is offered, will provide sufficient levels of Lysine and Methionine, which is where a broad-spectrum vitamin and mineral supplement/balancer, or a specifically designed hoof supplement containing amino acids can help to meet the horse’s requirements. Such products are often low in calories making them suitable for those prone to gaining weight.

FATTY ACIDS

Omega fatty acids are long chains of carbon and hydrogen atoms that form polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) that give structure to the cell walls in the body’s tissues and aid the absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K (NRC, 2007). Fatty acids are components of the cement that binds the individual cells of the hoof and also form a permeable barrier that controls hoof moisture level, making them important for hoof quality. As horses cannot produce their own PUFAs, they must be provided within their diet, making them essential nutrients. Fatty acids have numerous benefits to the horse with omega-3 fatty acids having an anti-inflammatory response, whilst omega-6 fatty acids are proinflammatory, making it more ideal to choose a feed or oil with a higher omega-3 to omega-6 ratio. Marine derived omega-3 sources, commonly from fish and algae, contain eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), whilst those obtained from plants, such as linseed, contain alpha-linolenic acids (ALA). Alpha-linolenic acids are the longest of the PUFAs and can be broken down by the horse to EPAs and DHAs, however the horse is not particularly efficient at undertaking this process, making it more beneficial to provide a marine based omega-3 source (Warren, 2015). Traditionally cod liver oil was used to provide such nutrients however producing fish oil is highly unsustainable and brings about a controversial matter, with horses being naturally vegan some owners may be hesitant to feed a fish-based product, whereas algae is an excellent vegan alternative.

VITAMINS

Biotin (also known as Vitamin B7 and Vitamin H) is the most widely researched vitamin with regards to hoof health, yet it also supports growth of the coat, mane and tail due to its role in the formation of keratin. Whilst B vitamins, including Biotin, are by-products produced from fibre fermentation within the horse’s hindgut, it may be beneficial to provide additional Biotin in the diet. In one of the first studies regarding Biotin, Buffa et al. (1992) using 24 horses, found that supplementing 15mg of Biotin compared to 7.5mg showed better hoof growth rates and hardness. Further studies showed that supplementing 1mg of Biotin per day to a 500kg horse is adequate to support general health (Geyer, 2005), however a study by Josseck et al. (1995) showed that feeding 20mg per day to a 500kg horse had a more positive effect on hoof health and growth. Reilly et al. (1998) found a 15% increase in hoof horn growth rate after 5 months, after supplementing ponies at a higher rate of 0.12mg/kg body weight, equivalent to 60mg for a 500kg horse. It is advised that horses who are prone to weak, brittle or cracked hooves, receive long term supplementation of Biotin to maintain the growth rate of the horn (Geyer and Schulze, 1994) as when supplementary dietary Biotin is reduced or removed, the hoof may once again deteriorate. When looking for an additional feed or supplement for hoof health it is advisable to select one with 20mg per day or above for a 500kg horse.

It is important to meet the requirements of all vitamins, not just Biotin, to maintain the general health of the horse, and is one reason it is necessary to provide feeds and supplements that provide balanced nutrients. Many vitamins are sensitive to ultraviolet light, therefore forage will lose a large proportion of its vitamin content during the harvesting process and these levels will continue to deplete over time in storage. Many nutrients within hay are also lost through the soaking process, so if this is a practice you use for your horse’s forage, evidence suggests that a vitamin and mineral supplement will support deficiencies and provide known amounts.

MINERALS

Zinc and Copper

Zinc is a trace mineral that is responsible for numerous roles within the equine body such as growth rates and cell division (Kellon, 1998). Zinc is involved in the uptake of amino acids and Sulphur, and thus the synthesis of keratin. For Zinc to be absorbed it must be provided in the correct ratio to Copper, another trace mineral, at 4 parts Zinc to 1 part Copper (4:1). Zinc can be found in high concentrations within the hoof tissue and so a deficiency can be easy to detect. Slow hoof growth, thin walls and weak horn can all indicate a Zinc deficiency (Kellon, 2019). Copper aids the formation of bone and connective tissues including the cross-links within keratin that give the hoof its strength and density, with deficiencies causing abnormalities in the bone, connective tissues and potentially reducing hoof growth (Kellon, 1998). Increased cases of laminitis, thrush and abscesses could also indicate Zinc and Copper deficiencies (Kellon, 2019). Some farriers have now even started to use Copper nails when shoeing horses due to Coppers potential antibacterial effect, although this depends on the type of shoe used. A study by Jancikova et al. (2012) using 16 Warmblood horses showed that providing supplemental Copper and Zinc increased the content of these trace elements found within the dry matter of the hoof horn.

A study by Higami (1999) found that horses were more likely to experience white line disease when consuming a low Copper and Zinc diet compared to those supplemented with raised levels of these trace minerals. UK soils are often low in Copper and Zinc which generally means that the forage grown in these soils are also low in these nutrients. Horses grazing such areas or consuming forage harvested from such land may be more susceptible to associated deficiencies, meaning an additional supply of such nutrients are required through the feed or supplementation.

Calcium and Phosphorus

Calcium is a macro mineral and is required in all horses’ diets to support the development of many structures within their body, such as bones, teeth and muscles, as well as for normal hoof growth. Within the actual hoof structure, Calcium is only present in very small quantities, yet it is vital to help make cross-links of Sulphur between proteins in the hoof horn (Geyer, 2005), in turn creating a stronger and healthier hoof. A study by Ley et al. (1998) showed that seasonal changes affected the Calcium content of hooves in 48 Thoroughbred horses, with horses showing a significantly higher Calcium content within their hooves during spring, summer and autumn compared to the winter, likely due to higher Calcium content within forage and grass.

We can see from table 1 that Calcium is a large proportion of the minerals required for a balanced diet which can vary significantly depending on the individual horse’s needs. Taking these variations into account will ensure that there is no deficiency. Young horses, breeding horses and those in hard work will require increased levels of Calcium and a deficiency may cause a loss of tubular structure within the inner walls of the hoof structure (Frape, 2010). It must not be forgotten that Calcium should be balanced with Phosphorus in the ratio at 2 parts Calcium to 1 part Phosphorus (2:1). If the Phosphorus intake is higher than that of Calcium, then Calcium absorption may be hindered leading to chronic Calcium deficiency, even if the actual level of Calcium in the diet meets requirements (NRC, 2007).

Image: Blemish in the hoof wall

Selenium

Selenium has become popular within equine supplements as it is an antioxidant that prevents the oxidation of fats and aids correct muscle development in the horse (NRC, 2007). We are all aware that providing a balanced diet is important, but it is just as important not to over supplement. As shown in table 1, the recommended maintenance daily feeding rate for the average 500kg horse is 1mg of Selenium. Horse owners must be careful not to over supplement their horse’s diets with Selenium as high levels are extremely toxic and Selenium toxicity can have detrimental effects on the hooves, leading to sloughing, cracking, and in severe cases shedding of the hoof wall (Frape, 2010). Geyer (2005) found that excess Selenium caused the decay of the hoof horn close to the coronet band. The levels of Selenium in soils can vary greatly, causing a range of concentrations in grazing and forages, making a further case for the benefits of testing your soil and forage for Selenium levels

METHYL SULPHONYL METHANE

Typically known for its joint supporting qualities, Methyl sulphonyl methane (MSM) is also high in biologically available Sulphur, which is important for keratin formation. Therefore, supplementation with MSM can help improve hoof quality (Frape, 2010).

SUMMARY

We have explored the nutritional needs for hoof health from general diet to more key nutrients, showing that with regards to correcting abnormalities or weaknesses, nothing is a quick fix. The addition of nutritional supplements presents many benefits which are seen through continued use over an extended period of time and which allow the renewal and growth of the whole hoof. It is clear that the provision of additional Biotin, amino acids, omega-3 fatty acids, as well as various minerals aid healthy hoof growth.

For any advice or questions you may have, please don't hestiate to reach out to our expert nutrition team. You can call 0800 585525 Monday-Friday 8:30am-5:00pm. Email [email protected], or send us a DM on social media.

REFERENCES

Anon (1998). Nutritional needs of the hoof. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 18(7): 456. doi.org/10.1016/S0737-0806(98)80037-3.

Buffa, E.A., Van Den Berg, S.S., Verstraete, F.J.M., & Swart, N.G.N. (1992). Effect of dietary biotin supplement on equine hoof horn growth rate and hardness. Equine Veterinary Journal, 24(6): 472-474. doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1992.tb02879.x

Butler, K.D., & Hintz, H.F. (1977). Effect of Level of Feed Intake and Gelatin Supplementation on Growth and Quality of Hoofs of Ponies. Journal of Animal Science. 44(2): 257-261. doi.org/10.2527/jas1977.442257x

Frandson, R.D., & Spurgeon, T.L. (1992). Anatomy and Physiology of Farm Animals,5th Ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, USA.

Frape, D. (2010). Equine Nutrition and Feeding, 4th Ed. Wiley- Blackwell, UK.

Geyer, H. (2005). Nutritional Management to keep the Hoof Health. In: A.Lindner (ed.). Applied Equine Nutrition: Equine Nutrition Conference (ENUCO) 2005. Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers. 43-58.

Geyer, H., & Schulze, J. (1994). The long-term influence of biotin supplementation on hoof horn quality in horses. Schweizer Archiv fur Tierheilkunde, 136(4): 137-149.

Hampson, B.A., Laat, M.A., Mills, P.C., & Pollitt, C.C. (2012). Effect of environmental conditions on degree of hoof wall hydration in horses. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 2: 435-438. doi:10.2460/ajvr.73.3.435

Higami, A. (1999). Occurrence of white line disease in performance horses fed low zinc and low copper diets. Journal of Equine Science. 10: 1-5. doi.org/10.1294/jes.10.1

Thirkell, J., & Hyland, R. (2017). A Preliminary Review of Equine Hoof Management and the Client–Farrier Relationship in the United Kingdom. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 59: 88-94. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2017.10.005

Jancikova, P., Horky, P., & Zeman, L. (2012). The effect of feed additive containing vitamins and trace elements on the elements profile and growth of skin derivatives in horses. Annals of Animal Science, 12(3): 381-391. doi:10.2478/v10220-012-0032-4

Josseck, H., Zenker, W., & Geyer, H. (1995). Hoof horn abnormalities in Lipizzaner horses and the effect of dietary biotin on macroscopic aspects of hoof horn quality. Equine Veterinary Journal, 27(3): 82-175. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1995.tb03060.x

Kellon, E.M. (1998). Equine Supplements and Nutraceuticals: A Guide to Peak Health and Performance Through Nutrition. United States of America, Breakthrough Publications.

Kellon, E.M. (2019). Feeding for Horse Hoof Health by Dr Kellon. Published on the Internet; https://forageplustalk.co.uk/feeding-horse-hoof-health-dr-kellon/. [Accessed 30 March 2021]

Lewis, L.D. (1995). Equine Clinical Nutrition: Feeding and Care. United States of America, Williams & Wilkins.

Ley, W.B., Pleasant, R.S., & Dunnington, E.A. (1998). Effects of season and diet on tensile strength and mineral content of the equine hoof wall. Equine Veterinary Journal, 26: 46-50.

Logie, S. (2017). Hoof wall separation disease. Equine Health, 35: 18-20. doi:10.12968/eqhe.2017.35.18

McDonald, P., Edwards, R.A., Greenhalgh, J.D.F., Morgan, C.A., Sinclair, L.A. & Wilkinson, R.G. (2011). Animal Nutrition, 7th Ed. Pearson Education Ltd.

NRC (2007). Nutrient Requirements of Horses, 6th Ed. Washington, USA, The National Academies Press

O’Grady, S.E., & Burns, T.D. (2021). White line disease: A review (1998-2018). Equine Veterinary Education, 33(2): 102-112. doi.org/10.1111/eve.13201

Reilly, J.D., Cottrell, D.F., Martin, R.J., & Cuddeford, D.J. (1998). Effect of supplementary dietary biotin on hoof growth and hoof growth rate in ponies: a controlled trial. Equine Veterinary Journal, 26: 51-57. doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1998.tb05122.x

Warren, H. (2015). Algae for Horses. Equine Health, 21: 10-13. Doi.org/10.12968/eqhe.2015.1